Elizabeth Warren plants a flag in California, as state's early primary scrambles the calendar

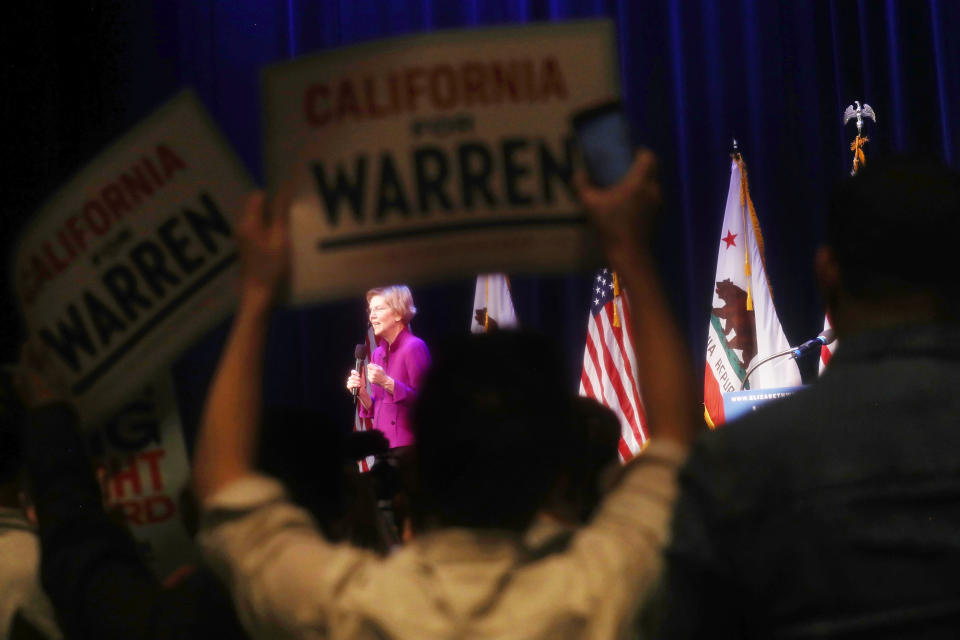

GLENDALE, Calif. — It could have been a rally in New Hampshire on the eve of the 2020 primary. There was the candidate, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, gripping the mic and pacing the stage in a cropped, purple, collarless coat. There was the brisk, biographical stump speech, polished to a stadium-ready shine. There was the peppy yet pointed playlist: “American Girl” by Tom Petty, Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror.” And then there was the crowd: a packed house of 1,400 — plus another 300 outside, according to the campaign — leaping to its feet whenever Warren delivered her well-honed applause lines about overturning Citizens United or making it easier to join a union.

The only indication that this wasn’t all happening in New Hampshire? The hundreds of red, white and blue “California for Warren” signs her staffers had ordered for the occasion.

The fact that a leading Democratic presidential contender spent Monday night rallying in this off-the-beaten-trail Los Angeles suburb is unusual enough; when Democrats visit deep-blue California, they tend drive straight from the airport to a closed-door, high-dollar Hollywood or Silicon Valley fundraiser, and then straight back to the airport.

But what’s really remarkable is not just that Warren bothered to rally here at all — it’s that she was doing it a full 379 days before the state’s 2020 primary.

The skill, scale and early timing of Warren’s event, California strategists tell Yahoo News, is one of the first clear signs that even though America’s most populous and progressive state is unlikely to be in play in next November’s election, it is already looming large in the Democratic nominating contest.

Much has been made of the reason why: California’s decision to move its primary from June to March 3. “In years past, the California primary was among the last in the nation, which meant it didn’t get much attention from candidates,” “Good Day LA” host Elex Michaelson said into a Fox 11 camera as he strode up the aisle prior to Warren’s speech, summing up the conventional wisdom. “But this time we’re going to be among the first — which could be a game-changer for American politics.”

Whether the 2020 California primary actually changes the game remains to be seen. The state’s huge delegate prize — nearly a quarter of the 2,026 needed to win the nomination — comes at a price. It is famously expensive to run statewide in California, home to 8.5 million Democrats spread along 850 miles of coastline and across eight major media markets. “For a contested election in California, campaigns will spend $30 million, $35 million — that’s the norm,” says veteran consultant Bill Carrick, who has advised Sen. Dianne Feinstein and Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti. Which is why “no candidate can afford to run the equivalent of a governor's race here,” explains Yusef Robb, a key Garcetti strategist who helped the mayor explore (and eventually rule out) a presidential run. “They have to divide their resources nationwide.”

The second factor to consider is the complex way California actually awards its delegates. The primary results will determine how 416 of the state’s 492 delegates are divvied up. The majority of that total — 272 — will be divided among California’s 53 congressional districts, but not evenly: blue districts will award more delegates than red or purple districts. The remaining 144 pledged delegates, meanwhile, will be apportioned among candidates who clear 15 percent of the statewide vote. In other words, California is decidedly not a winner-take-all state — meaning it is unlikely to deliver a “game-changing” knockout punch.

Then there’s timing to think about. Yes, California will vote on the first Tuesday in March, right after the four early-primary states of Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina and Nevada. But so will Alabama, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont and Virginia; Colorado and Minnesota could eventually join them. This crowded Super Tuesday schedule, full of delegate-rich contests, suggests that “March 3rd will probably become the functional equivalent of a national primary, with all the logistical problems, all the organizational problems and all the immediate costs that entails,” says Carrick. “Everyone is going to have to decide where they're going to play and where they're going to put their resources” — almost certainly diluting California’s impact.

Finally, it’s worth noting that one of the Democratic Party’s top 2020 prospects, Kamala Harris, hails from the Bay Area, represents California in the U.S. Senate and is already playing to win here next March. Harris’s political strategists, Sean Clegg and Ace Smith, have won a dozen or so statewide races; Harris herself has won three (two for attorney general, one for senator). No other campaign comes close. With that in mind, Harris has held seven California fundraisers to date; secured endorsements from Gov. Gavin Newsom, Reps. Barbara Lee, Ted Lieu, Nanette Barragan and Katie Hill, and 21 of the 28 Democrats in the state Senate; and “brought on a top delegate expert and senior strategist with deep ties to powerful organized labor groups in the state,” according to a recent Politico report.

“Our strategy runs straight through California, and we plan to aggressively defend our home state turf from donors to political leadership to superdelegates to organizations and their underlying memberships,” Clegg told the site. “We believe the early primary, early voting and the cost of communicating will make it virtually impossible for all but the top two or three candidates to play in the state in a meaningful way.”

The idea, it seems, is to spook the rest of the field and transform Harris’s early advantages into early votes. (Vote-by-mail will start in California the same day as the Iowa caucuses, and harvesting ballots — especially in delegate-rich blue districts — will require lots of organization.) “Ace and Sean know how to do this better than anyone in the state,” says Dan Schnur, a former spokesman for John McCain and recent director of the Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics at the University of Southern California. “They have an infrastructure in place to build that firewall even while Harris is in other parts of the country.”

Given all that, why did Warren touch down in Glendale? And why do folks like Bill Carrick consider her visit a “harbinger of what’s to come”?

“Before, people might have flown here for money, and a couple paragraphs would be written up in Variety about that visit,” says Robb. “But now I believe you’re going to see a lot more high-profile visits — and earlier.”

Rarely has campaigning in California, long home to some of the country’s most comfortable and complacent progressives, made much sense for a Democratic primary candidate; it’s usually been dismissed as a waste of time and resources. (One exception: Sen. Bernie Sanders’s decision to barnstorm the state right before the 2016 primary, which earned him activist and union support that could pay off in 2020.)

Yet in the wake of Donald Trump’s 2016 upset — and last year’s midterm backlash, when fired-up, anti-Trump Democrats swept seven California House Republicans out of office — unprecedented grassroots energy has scrambled the old math.

“The calculation that a presidential campaign used to make is whether it was worth scheduling a few living-room visits before and after the big-ticket fundraiser,” says Schnur. “But now the incentive to schedule a big rally is much greater, because the level of enthusiasm among Democratic activists is off the charts. A candidate who may have been lucky to fill a living room in a previous presidential campaign can probably fill a high school gym — or even a theater — without much problem.”

The upside of such engagement isn’t just a lively event that looks good on the local news. It’s practical as well. All 1,700 attendees at Warren’s Glendale event were “encouraged” to RSVP, and to share their emails and phone numbers while doing so; the thinking is that Angelenos and other Californians eager to release all their pent-up “resistance” energy and finally participate in a campaign will someday become online donors (and maybe even volunteers or organizers). In 2018, for instance, Texas Senate candidate and possible 2020 presidential contender Beto O’Rourke raised more money ($6.15 million) from California than from any other state except Texas, and much of that cash came via the internet in small-dollar increments.

Either way, connecting in real life can’t hurt. “Everybody gets a ton of campaign emails these days,” says Carrick. “What candidates like Warren are trying to do is to make sure they have some relationship to reality — that people in California can feel and touch the campaign.”

Eventually, the benefits of engaging early and often in California will put any out-of-state candidates who survive February in position to compete with Harris for delegates — or to overtake her.

“It's so far out that I don't think anyone's position is fixed or ordained by any means,” says Robb. “And the fact is, how candidates perform in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina and Nevada is going to have a profound impact on the decisions that Californians make, because more than anything else, California Democrats want to win the White House. They don't necessarily need their neighbor in the White House.”

It’s entirely possible that Harris will stumble in the early states, or that expectations will be so high for her in California that the second-place finisher will get more media attention, or that whoever wins the most nationwide delegates on Super Tuesday will be declared the day’s winner. In each of those scenarios, any competing candidate who has figured out how to maximize his or her proportional, district-by-district California delegate haul will stand to gain — which is why, as Politico recently reported, “advisers to at least six Democratic campaigns or prospective candidates have begun speaking to Democratic strategists with California campaign experience, asking about the state’s delegate math, ballot-collection practices and early voting.”

That part, at least, isn’t new. The last time California held a Super Tuesday primary was in 2008; Bill Carrick remembers getting an early call from Jeffrey Berman, Barack Obama’s director of delegate selection. “We went through every single congressional district,” Carrick says. “Some of them they had polling from; some of them they didn’t, so we were just eyeballing the historic dynamics. The point was to come up with the target districts where Obama needed to compete in order to get the maximum number of delegates.” On primary day, longtime favorite Hillary Clinton won California’s popular vote by more than 8 percentage points, but Obama still secured 166 delegates — enough to propel him past Clinton in the overall Super Tuesday tally. He went on to win the Democratic nomination.

The difference is, back then, Obama never campaigned in California, choosing instead to send surrogates such as his wife, Michelle, and Sen. Ted Kennedy. This time around, Warren has already broken with that tradition — and while she may be the first, she won’t be the last.

“The fact that a crowd like Warren’s turned out on a weeknight in the outer suburbs of Los Angeles a year before the primary — that’s extraordinary,” says Schnur. “But it tells you more about California’s Democratic electorate than it does about the candidate. A year from now they may or may not be Warren supporters. But they're going to be at the barricades for someone.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Ann Coulter: ‘Lunatic’ Trump could be challenged in 2020 — from the right

As concerns grow about faltering U.S. support for UAE, China steps in to fill the void

Habitat for sale: An oil and gas group calls the tune at the Interior Department

Crackdown on opioids has its own victims: People who need them to live

As 5G war with China heats up, could a Cold War-inspired plan be the solution?

PHOTOS: Eye in the sky: Unusual shots of animals from above will leave you in awe